My Research Paper

Here it is:

“The Most Celebrated Edifice in the World”

A photo of the Pantheon at night.

The Roman Civilization has undoubtedly impacted how people experience their lives today. But nowhere is this impact stronger than in the buildings and art that we see. One particular building has had a profound influence on such monumental structures such as St. Peter’s building in

understanding one possible purpose of the pantheon might enable us to discern some basic principles that drive the pantheon’s appeal. One purpose of the Pantheon is to represent authority. By demonstrating power, relating the Roman Empire to the heavens and combining both Greek and Roman architecture into one building, Hadrian built the Pantheon as a representation of

However, before I begin, I’d like to define what I’m arguing about. Many disagreements arise between two parties because they are using different definitions for their terms, and so before we begin I’d like to explain what I mean by “authority”. I define authority as the ability of someone to easily extract obedience from others based off of others’ belief that this person is for some reason allowed to command them. Hadrian would certainly need as much authority as possible in order to execute his orders with minimal resistance.

Photo of a bust of Hadrian

Now that we know what we’re arguing about, let us all play a quick game of catch-up as we review the Pantheon’s dramatic history. The emperor who first built the pantheon was actually Marcus Agrippa. Agrippa built the Pantheon in 25 BC., but after burning down, being restored, and again being struck down by lightning, the Pantheon could hardly be called a building when Hadrian came to power (DuTemple 9). Recognizing that this charred rubble might not reflect well on the glory of the

exactly building began, but it is generally agreed that the idea of the Pantheon was Hadrian’s, and that building started around 118 AD and ended around 128 AD (MacDonald 12)(DuTemple 24). Time passed, and eventually the Pantheon fell into disrepair along with the

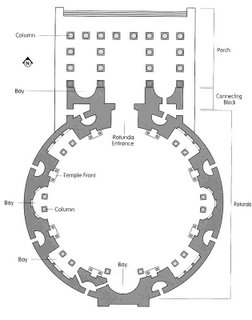

A marked floor plan of the Pantheon

The Pantheon itself is made up of three distinct sections: the porch, the domed rotunda, and the intermediate block which connects the two. The Pantheon was originally situated on top of a flight of steep stairs, which led to the front porch. This flight of stairs gave the ancient roman viewer quite an imposing impression of the Pantheon. The Pantheon’s front porch is similar to a traditional Roman temple borrowed from the Greek form. In front are eight gigantic marble monolithic columns which carry a triangular stone pediment. Behind the first row of columns are two additional rows of four columns each which form three aisles leading up to the temple front (MacDonald 28). The marble monoliths represent immense power because of their size, which only a very powerful and wealthy empire could afford to quarry, carve, and then roll on logs all the way from

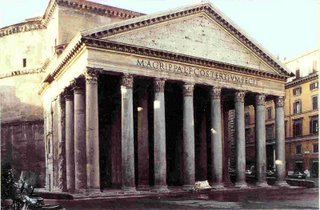

The Pantheon's porch, and Agrippa's inscription

The front of the stone pediment bears its founder’s signature: “M AGRIPPA LF COS TERTIUM FECIT (Marcus Agrippa, consul for the third time, built this)” (Macdonald 13). Why Hadrian chose Agrippa’s name instead of his own is a mystery. One scholar argues that “[Hadrian] wanted it understood as a restoration of Agrippa’s building is in keeping with his intention of vindicating the Imperial order” (McEwen 60). Because Marcus Agrippa was a close friend of Octavian Augustus,

One other interesting fact about the Pantheon’s porch is that Hadrian made a special effort to turn the Pantheon’s porch around to make it face north, which in the Etruscan sky system is where Janus, the god of doorways, resides (McEwen 62). To ancient Romans, for whom the Etruscan sky system was quite important, this coincidental cardinality served to intimately connect the Pantheon with the sky and thus the gods.

Two of the best ways to demonstrate authority are to demonstrate power and a connection to the gods, because both imply control over others. Because the Pantheon’s porch demonstrates both of the above aspects and connects itself to

But the most amazing part of the Pantheon is the domed rotunda that the porch leads into. From the outside, the rotunda is a cylindrical wall of brick with openings strewn here and there, and a bowl-shaped dome (MacDonald 33). A little more than half of the dome is made up of step-like circular rings, which was yet another engineering trick used in the Pantheon to support the massive dome. (MacDonald 33). At the very top of this dome is a giant hole called an oculus 30 feet in diameter which leads inside.

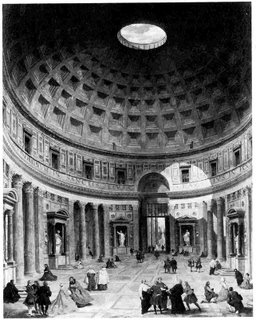

A painting of the Pantheon's dome (interior).

The dome’s modest bowl-shaped exterior completely belies the spherical dome inside. The rotunda itself is a behemoth of a structure “The rotunda of the Pantheon rests of a large circle of concrete There are, by calculation about 10,000 metric tons of it”(McEwen 63). These 10,000 metrics tons were needed simply as a foundation to hold up the building. The rotunda itself was 147 feet in diameter, and was as tall as it was wide. The large proportions of the building are yet another display of the Empire’s vast resources and power.

The pantheon's spherical dome with its square recesses (called coffers)

The spherical dome, tiled with small square recesses, is awe-inspiring. During Hadrian’s time, building such a perfectly shaped dome must have been an incredible challenge, and would only have been done for a very good reason. One possibility for making the dome spherical was to connect the Pantheon more closely with the heavens, which the Romans believed to be spherical at the time (DuTemple 6). Cassius Dio, a historian who lived about 100 years after Hadrian, says, “[the Pantheon’s] vaulted roof resembles the heavens” (McEwen 65). Some scholars have even gone as far as arguing that there are sixteen divisions in the Pantheon which correspond to the 16 parts of the Etruscan sky, which was the celestial world in which the gods resided (McEwen 61). The oculus in the very center of the dome is another costly design choice (it necessitated a drainage system for when it rained) which probably was meant to connect the Pantheon to the heavens. “The sun, said the ancients, is the eye of Zeus, and in Hadrian’s Pantheon the greatest of gods was epiphanized in light.” (MacDonald 91). Including the oculus brought the greatest of the gods down to earth in an almost tangible form. The Pantheon’s dome, like the porch, represents power and again links the

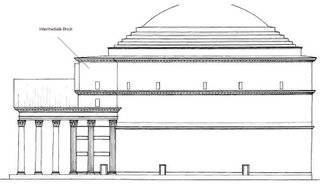

A diagram of the Pantheon (side view) with the intermediate wall marked

The third and most intriguing portion of the Pantheon is the intermediate block which connects the porch to the Rotunda. It is a rectangular block with some stairs and two rooms. What is fascinating though, is what this connection of the porch and dome implies. By combining the more roman dome with the Greek temple entrance, Hadrian was blending the two greatest civilizations together to create the most symbolically powerful building in

Of course, the Pantheon wasn’t just a monument for ancient Romans to look at; it was actually used by both Hadrian and the public for many purposes. Ostensibly, the Pantheon is a Roman temple. In fact the etymology of the word ‘pantheon’ means ‘all gods’, and it was, as its name suggested, a temple for all the gods (DuTemple p9). However, “the Pantheon also served as one of the emperor’s official places of business. “Hadrian wanted to see the heavens and the

However, Hadrian probably wouldn’t spend so much of

To maintain power, Hadrian needed a building to demonstrate that he was still incredibly powerful and should be obeyed. And since “the Roman Empire was at the height of its powers…A newly designed Pantheon, perfect in its construction and stunning in its beauty, could reflect the symmetry and power of the Roman Empire”(Dutemple 9).

One final motivation for building the Pantheon as a symbol for authority was that Hadrian needed to support his view of

A photo of Urban VIII's inscription

At the back of the Pantheon’s porch, just to the right of the great bronze doors is an inscription made in 1632, created by Urban VIII, which reads, “The Pantheon [is] the most celebrated edifice in the world” (MacDonald 94). This statement can be confirmed with a quick glance at the illustrations of any book on the history of architecture to see the countless domed rotundas with temple-front porches (MacDonald 94). “It is one of the few archetypal images in Western culture” (MacDonald 94). Why has it been so influential? Nobody knows for sure, but we do have a few hints. First, “the Pantheon motif can be seen wherever authority, ecclesiastical or political demand a recognizable, stately architectural imagery” (MacDonald 131). Second, that by connecting the Greek and Roman cultures, and

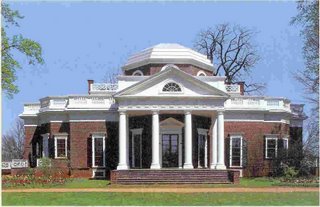

Thomas Jefferson's Monticello. Can you see the resemblence?

Works Cited

Davies, Paul, David Hemsoll, and Mark Wilson Jones, “The Pantheon: Triumph of

DuTemple, Lesley. The Pantheon.

Leacroft, Helen and Richard. The Buildings of Ancient

MacDonald, William. The Pantheon: Design, Meaning, and Progeny.

McEwen, Indra Kagis, "Hadrian's Rhetoric I: The Pantheon", RES, vol. 24, Autumn, 1993.

Perowne, Stuart. Hadrian.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home